Collection: Sir Terry Frost RA

Terry Frost Art Prints & Paintings for Sale

Original silkscreen prints from one of Britain's most successful and highly acclaimed 20th Century artists.

"Prints were an essential element of Frost's oeuvre - he believed that painting and printmaking were inseparable and that each medium informed the other." - Dominic Kemp

Collapsible content

Collapsible content

More on Cyril Power and Sybil Andrews

Cyril Power was born in London, the eldest child of an architect father, and a mother who encouraged the young Power’s interest in the arts – in drawing in particular (there are sketchbooks which date back to 1886) but also in music, in the piano and violin – two instruments Power was to become proficient in playing.

Power followed in the family tradition, became an architect and worked in his father’s practice. He excelled here, and in 1900 won The Sloane Medallion, awarded by the Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA) for his design for an art school. He also wrote and published a three-volume work, illustrated with his drawings, on the ‘History of English Mediaeval Architecture’.

Power married Dorothy Mary Nunn in 1904 with whom he was to raise four children. They lived mostly in London – in Putney and then Catford – but for a period in Bury St. Edmunds, Suffolk, where Power was to meet and then work with life-long friend and fellow artist, Sybil Andrews.

Both artists, Power and Andrews, moved to London and in 1925 they helped Iain McNab and Claude Flight set up The Grosvenor School of Modern Art in Warwick Square. Andrews become the School Secretary, and Power the principle lecturer. He taught on the form and structure of buildings; on historical ornament and on architectural styles. But he, along with Andrews, also attended Claude Flight’s classes, at the School, in linocutting.

Soon it was this medium, linocutting, which, with Claude Flight’s ability both as supreme exponent of the art, and as teacher, attracted the (now famous) ‘Grosvenor’ artists from far and wide – most notably, due to advertisements in ‘The Studio’, from Australia and New Zealand.

The ‘First Exhibition of British Lino-Cuts’ was mounted in June 1929 at The Redfern Gallery, London, and a series of exhibitions were then held annually at both The Redfern and The Ward Gallery. These attracted considerable interest, and commissions for Power’s and Andrew’s work come in from The London Passenger Transport Board. A series of prints were created on the theme: sporting venues reached by the Underground, and the prints were all signed ‘Andrew Power’.

Architecture was the subject of most of Power’s early linocuts, such as ‘At Lavenham’ (1928) and ‘Westminster Cathedral’ (1928); but with Power’s and Andrew’s posters on the sporting venues the interest in speed and movement in his work first became evident. This vorticist’s concern, not only with speed and movement, but with the modern and the urban, Power was to develop further: in ‘Whence and Whither?’, ‘The Merry-Go-Round’ and in the exceptional ‘Tube Station’ and ‘The Sunshine Roof’ – amongst his best works – all ingredients are present.

Power continued to teach and work, in oils, principally, after World War Two, and produced some ninety paintings in the last years of his life. He died in London, May 1951.

Sybil Andrews’s [1898-1992] interest in art began whilst working as an oxyacetylene airline welder in the First World War. During this time she took John Hassall’s* art correspondent course which introduced her to a number of different artistic media, and set her on the path towards a career as an artist. After the War she returned to her birthplace, Bury St. Edmunds, in Suffolk. Here she met Cyril Power who would influence her work, and with whom she would share a workshop for much of her early working life. Power and Andrews were colleagues who would later collaborate on commissions from The London Passenger Transport Board, and they would jointly sign their work with the pseudonym ‘Andrew Power’.

Wishing to pursue her interests in art Andrews enrolled at Heatherley’s School of Fine Art, London. Here she explored relief printing, particularly woodcut printing, under the tutelage of William Kermode. But it was not until she became school secretary and attended Claude Flight’s linocut classes at the Grosvenor School of Modern Art that Andrews really found her métier, and she quickly became another acolyte (see Artists Lill Tschudi / Cyril Power) of Flight’s enthusiasm for the colour linocut.

In approach, Andrews’ linocuts evidence an assimilation of the formal language as taught by Flight. Linocuts are produced by a successive pressing of separately carved linoleum blocks, each differentially coloured, onto paper; and as such they are not that different to wood or metal blocks pressed onto paper. But, whereas up until that point printmakers had often used many blocks and sought to create an effect which mimicked works in watercolour and oil painting, Flight taught that it was better to use fewer blocks (typically only three or four). He argued that in so doing, the process of creation could itself became evident, and that this transparency was important. Another innovation of Flight’s – and one which is now recognised as characteristic of the Grosvenor School prints as a whole – was the abandonment of a key block. Before Flight (and for all Japanese woodblock prints, and indeed for most European woodcut prints) a key block was almost always used. This block provided structure and a black outline for the main shapes in the print. But Flight soon found this unnecessary and obtrusive, and argued that the key block served only to interrupt and divide the colours in such a way as to detract from the overall harmoniousness of the print.

Whilst Andrews’ works evidence this assimilation of Flight’s formal language, they often depart from a depiction of the kinds of subjects – the dynamism of the modern world, its concern with speed and with technological advances – that Flight encouraged. Instead, Andrews more often sought to capture the rhythms and living movements of the human figure.

She explored various sporting activities to this end, including football, horseback riding and motorcycle racing, as also activities associated with men’s physical work (see Football 1937; Racing 1934, and Speedway 1934 and The Winch 1930).

During the Second World War Andrews worked in a shipyard where she met her husband, and soon after (1947) the couple emigrated to the remote logging town of Campbell River on Vancouver Island, Canada. En route to her new home blocks for several of her prints partially melted in the over-hot hold of the ship. But she experienced no such misfortune to her artistic career when she arrived in Canada: there she achieved, at least at first, a large following which lasted well into the 1950’s. In the ‘60’s she fell into obscurity, but was rediscovered in the 1970’s. She died in 1992 leaving a body of work totalling almost 80 linocuts. Since then Sybil Andrews’ work has met with wide critical acclaim and ever increasing popularity. Her colour linocuts were featured extensively in the recent (2008) Fine Arts, Boston/ Metropolitan, New York British Prints From the Machine Age – Rhythms of Modern Life 1914–1939 exhibition, and her work is held in major collections around the world.

-

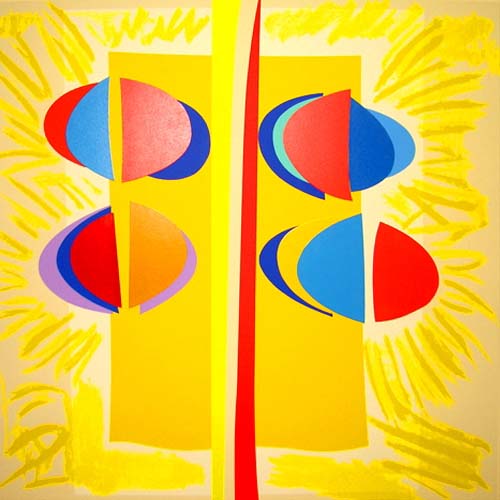

Sir Terry Frost - Blue Love Tree

Regular price £3,500.00 GBPRegular priceUnit price / per -

Sir Terry Frost - Sun Tree

Regular price £3,500.00 GBPRegular priceUnit price / per -

Sir Terry Frost - Carlyon Sunshine

Regular price £2,950.00 GBPRegular priceUnit price / per -

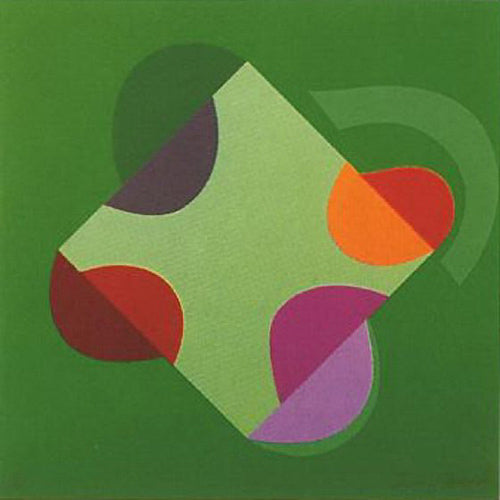

Sir Terry Frost - Development of a square within a square (green)

Regular price £1,200.00 GBPRegular priceUnit price / per -

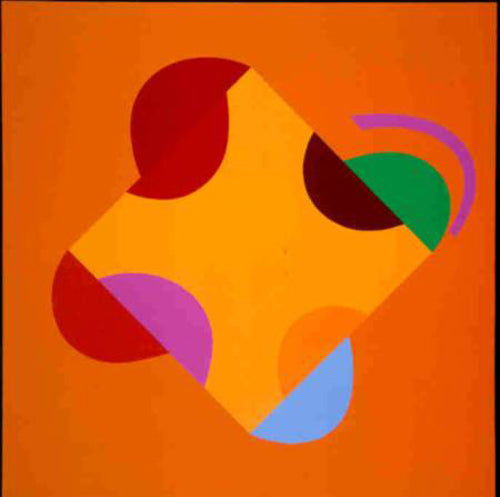

Sir Terry Frost - Development of a square within a square (orange)

Regular price £1,200.00 GBPRegular priceUnit price / per -

Sir Terry Frost - Development of a Square within a square (red)

Regular price £1,200.00 GBPRegular priceUnit price / per